New Orleans In The Civil War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

New Orleans Civil War photo albumConfederate Memorial Hall museum"The Washington Artillery, 5th Company, at the Battle of Perryville"

€”Article by Civil War historian/author Bryan S. Bush

Online exhibit about the Civil War

at

''New Orleans, the Place and the People''

(1895) *Henry Rightor

(1900) *John Smith Kendall

(1922) * Clara Solomon and Elliott Ashkenazi (ed.), ''The Civil War diary of Clara Solomon : Growing up in New Orleans, 1861-1862.'' Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press (1995) . *

New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, was the largest city in the South, providing military supplies and thousands of troops for the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

. Its location near the mouth of the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

made it a prime target for the Union, both for controlling the huge waterway and crippling the Confederacy’s vital cotton exports.

In April 1862, the West Gulf Blockading Squadron

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederate States of America, Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required ...

under Captain David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut (; also spelled Glascoe; July 5, 1801 – August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. Fa ...

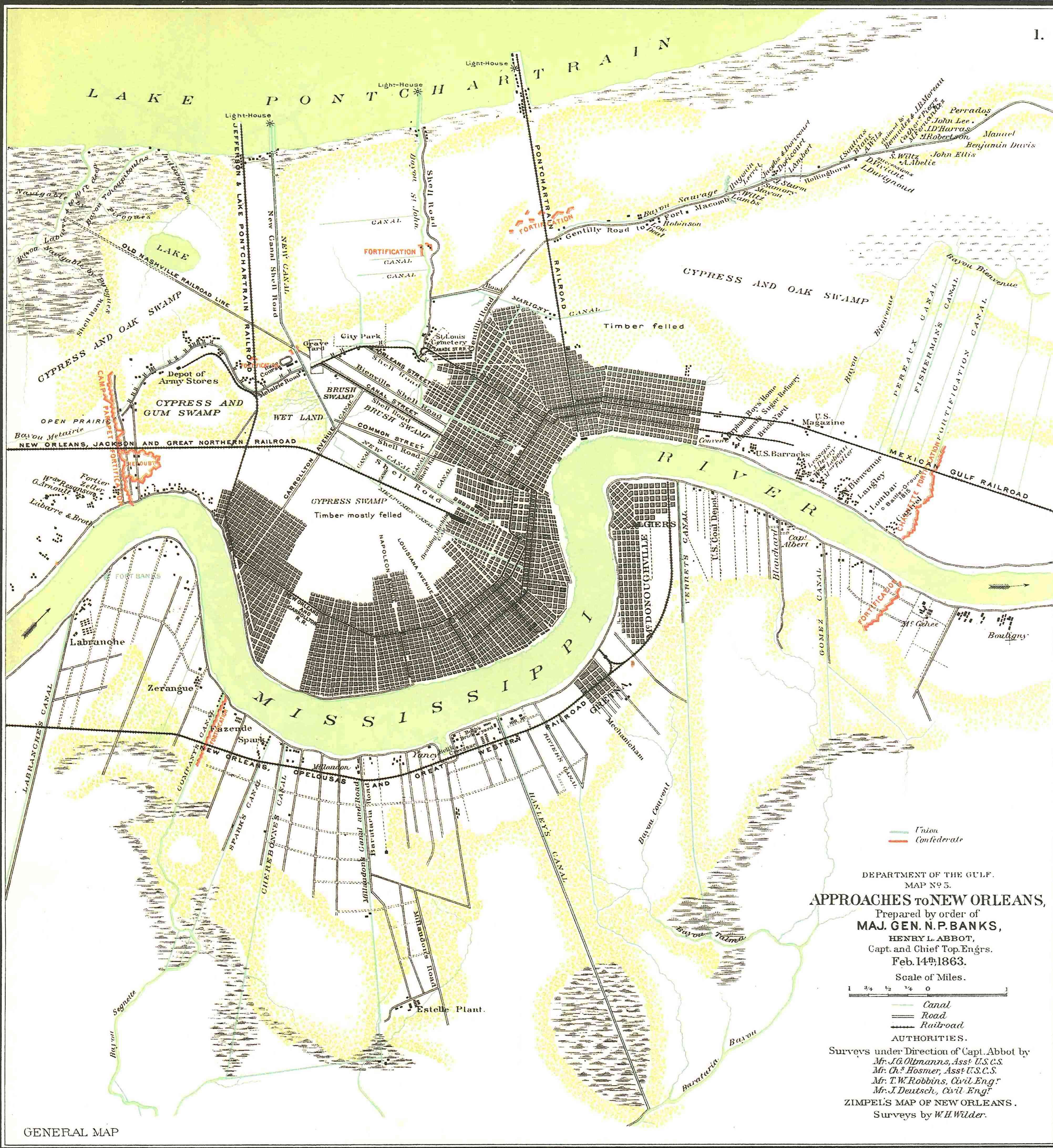

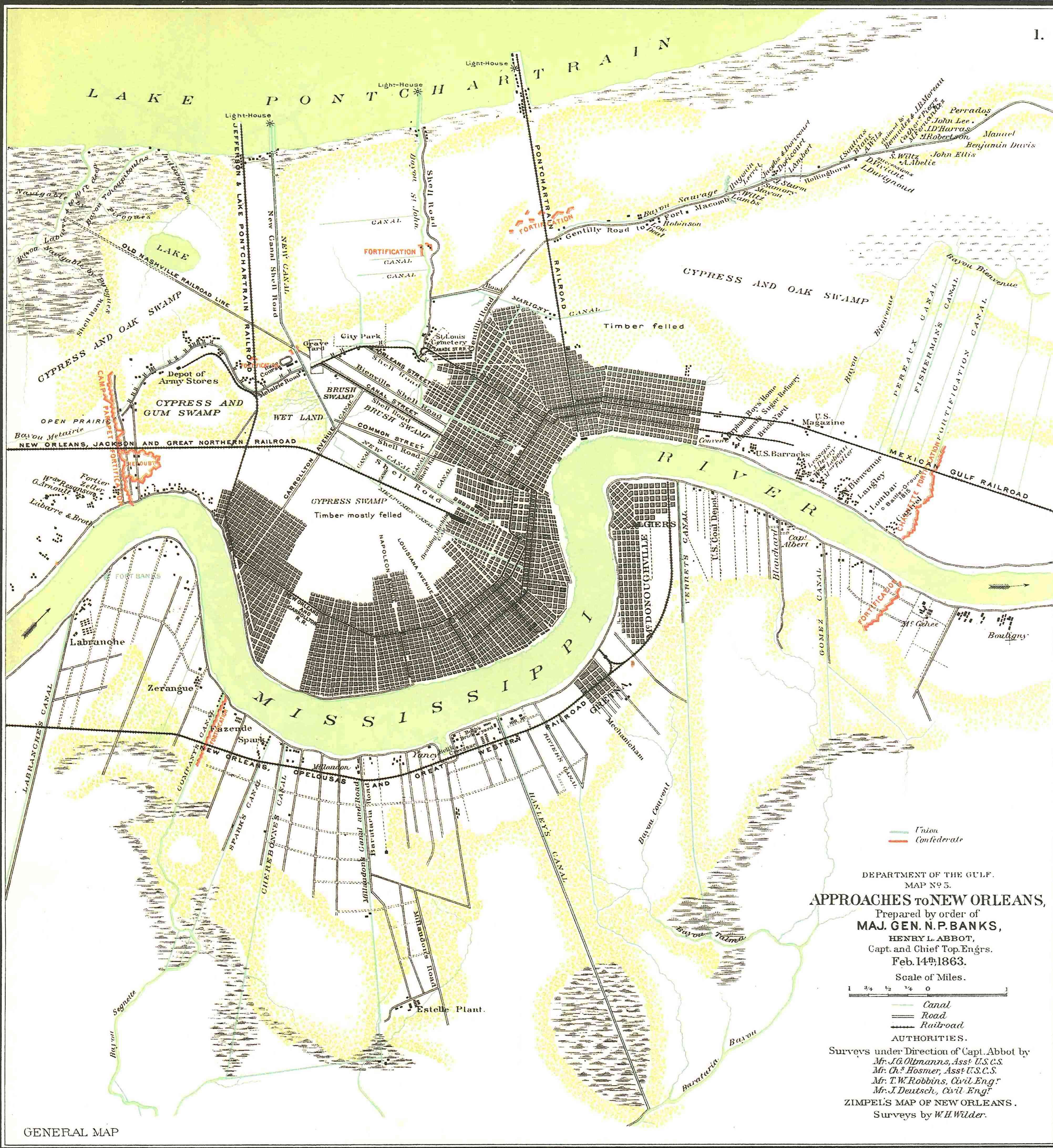

shelled the two substantial forts guarding each of the river-banks, and forced a gap in the defensive boom placed between them. After running the last of the Confederate batteries, they took the surrender of the forts, and soon afterwards the city itself, without further action. The new military governor, Major General Benjamin Butler, proved effective in enforcing civic order, though his methods aroused protest everywhere. One citizen was hanged for tearing down the US flag, and any woman insulting a Federal soldier would be treated as a prostitute. Looting by troops was also rife, though apparently not with Butler’s approval. He was eventually replaced by Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union general during the Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, ...

, who somewhat improved relations between troops and citizens, but military occupation had to continue well after the war.

The prompt surrender of the city had saved it from serious damage, so it remains notably well-preserved today.

Early war years

The earlyhistory of New Orleans

The history of New Orleans, Louisiana, traces the city's development from its founding by the French in 1718 through its period of Spanish control, then briefly back to French rule before being acquired by the United States in the Louisiana P ...

was one of uninterrupted growth. In the 1850 census, New Orleans ranked as the 6th largest city in the United States, with a population reported as 168,675. It was the only city in the South with over 100,000 people. By 1840 New Orleans had the largest slave market in the nation, which contributed greatly to its wealth. During the antebellum years, two-thirds of the more than one million slaves who moved from the Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern and lower Midwestern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, econom ...

in forced migration

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

to the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the war ...

were taken in the slave trade. Estimates are that the slaves generated an ancillary economy valued at 13.5 percent of the price per person, generating tens of billions of dollars through the years.

Antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ...

New Orleans was the commercial heart of the Deep South, with cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

comprising fully half of the estimated $156,000,000 (in 1857 dollars) exports, followed by tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

and sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

. Over half of all the cotton grown in the U.S. passed through the port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

of New Orleans (1.4 million bales), fully three times more than at the second-leading port of Mobile

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobile ( ...

. The city also boasted a number of Federal buildings, including the New Orleans Mint

The New Orleans Mint (french: Monnaie de La Nouvelle-Orléans) operated in New Orleans, Louisiana, as a branch mint of the United States Mint from 1838 to 1861 and from 1879 to 1909. During its years of operation, it produced over 427 million ...

, a branch of the United States Mint

The United States Mint is a bureau of the Department of the Treasury responsible for producing coinage for the United States to conduct its trade and commerce, as well as controlling the movement of bullion. It does not produce paper money; tha ...

, and the U.S. Custom House.''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'', February 16, 1861

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

voted to secede

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

from the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

on January 22, 1861. On January 29, the Secession Convention reconvened in New Orleans (it had earlier met in Baton Rouge

Baton Rouge ( ; ) is a city in and the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-sma ...

) and passed an ordinance that allowed Federal employees to remain in their posts, but as employees of the state of Louisiana. In March, Louisiana ratified the Constitution of the Confederate States

The Constitution of the Confederate States was the supreme law of the Confederate States of America. It was adopted on March 11, 1861, and was in effect from February 22, 1862, to the conclusion of the American Civil War (May 1865). The Confede ...

. The New Orleans Mint

The New Orleans Mint (french: Monnaie de La Nouvelle-Orléans) operated in New Orleans, Louisiana, as a branch mint of the United States Mint from 1838 to 1861 and from 1879 to 1909. During its years of operation, it produced over 427 million ...

was seized; it was used during 1861 to produce Confederate coinage, particularly half-dollars. Since the dies were not changed, these are indistinguishable from 1861-O (the raised O indicating New Orleans) halves minted by the U.S. government. (Using a different reverse die, an unknown number of true Confederate half-dollars were minted, before the silver bullion

Bullion is non-ferrous metal that has been refined to a high standard of elemental purity. The term is ordinarily applied to bulk metal used in the production of coins and especially to precious metals such as gold and silver. It comes from t ...

ran out. See New Orleans Mint

The New Orleans Mint (french: Monnaie de La Nouvelle-Orléans) operated in New Orleans, Louisiana, as a branch mint of the United States Mint from 1838 to 1861 and from 1879 to 1909. During its years of operation, it produced over 427 million ...

.)

New Orleans soon became a major source of troops, armament, and supplies to the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

. Among the early responders to the call for troops was the "Washington Artillery

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered ...

," a pre-war militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

company

A company, abbreviated as co., is a Legal personality, legal entity representing an association of people, whether Natural person, natural, Legal person, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common p ...

that later formed the nucleus of a battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

in the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

. In January 1862, men from the free black community of New Orleans formed a regiment of Confederate soldiers called the Louisiana Native Guard. Although they were denied battle participation, the Confederates used the Guard to defend various entrenchments around New Orleans. Several area residents soon rose to prominence in the Confederate States Army, including P.G.T. Beauregard

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (May 28, 1818 - February 20, 1893) was a Confederate general officer of Louisiana Creole descent who started the American Civil War by leading the attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Today, he is commonly ...

, Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, serving in the Weste ...

, Albert G. Blanchard

Albert Gallatin Blanchard (September 6, 1810 – June 21, 1891) was a general in the Confederate army during the American Civil War. He was among the small number of high-ranking Confederates to have been born in the North. He served on the ...

, and Harry T. Hays

Harry Thompson Hays (April 14, 1820 – August 21, 1876) was an American Army officer serving in the Mexican–American War and a general who served in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War.

Known as the "Louisiana Tigers," his brigad ...

, the commander of the famed Louisiana Tigers infantry brigade which included a large contingent of Irish American

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

New Orleanians.

The city was initially the site of a Confederate States Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the Navy, naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the Amer ...

ordnance

Ordnance may refer to:

Military and defense

*Materiel in military logistics, including weapons, ammunition, vehicles, and maintenance tools and equipment.

**The military branch responsible for supplying and developing these items, e.g., the Unit ...

depot. New Orleans shipfitters produced some innovative warships, including the ''CSS Manassas

CSS ''Manassas'', formerly the steam icebreaker ''Enoch Train'', was built in 1855 by James O. Curtis as a twin-screw towboat at Medford, Massachusetts. A New Orleans commission merchant, Captain John A. Stevenson, acquired her for use as a pri ...

'' (an early ironclad

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

), as well as two submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s (the Bayou St. John submarine

The Bayou St. John Confederate Submarine is an early military submarine built for use by the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War.

Description

The submarine is constructed of riveted iron, long, wide and deep, with a ha ...

and the ''Pioneer'') which did not see action before the fall of the city. The Confederate Navy actively defended the lower reaches of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, during the Battle of the Head of Passes

The Battle of the Head of Passes was a bloodless naval battle of the American Civil War. It was a naval raid made by the Confederate river defense fleet, also known as the “mosquito fleet” in the local media, on ships of the Union blockade s ...

.

Early in the Civil War, New Orleans became a prime target for the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

and Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral zone, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and ...

. The U.S. War Department

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet department originally responsible for the operation and maintenance of the United States Army, a ...

planned a major attack to seize control of the city and its vital port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

, to choke off a major source of income and supplies for the fledgling Confederacy.

Fall of New Orleans

The political and commercial importance of New Orleans, as well as its strategic position, marked it out as the objective of aUnion

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

expedition soon after the opening of the Civil War. Captain David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut (; also spelled Glascoe; July 5, 1801 – August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. Fa ...

was selected by the Union government for the command of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederate States of America, Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required ...

in January 1862. The four heavy ships of his squadron (none of them armored) were, with many difficulties, brought to the Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South, is the coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The coastal states that have a shoreline on the Gulf of Mexico are Texas, Louisiana, Mississ ...

and the Lower Mississippi River

The Lower Mississippi River is the portion of the Mississippi River downstream of Cairo, Illinois. From the confluence of the Ohio River and Upper Mississippi River at Cairo, the Lower flows just under 1000 miles (1600 km) to the Gulf of ...

. Around them assembled nineteen smaller vessels (mostly gunboats

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to shore bombardment, bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for troopship, ferrying troops or au ...

) and a flotilla

A flotilla (from Spanish, meaning a small ''flota'' (fleet) of ships), or naval flotilla, is a formation of small warships that may be part of a larger fleet.

Composition

A flotilla is usually composed of a homogeneous group of the same class ...

of twenty mortar boats under Commander David Dixon Porter

David Dixon Porter (June 8, 1813 – February 13, 1891) was a United States Navy admiral and a member of one of the most distinguished families in the history of the U.S. Navy. Promoted as the second U.S. Navy officer ever to attain the rank o ...

.

The main defenses of the Mississippi River consisted of two permanent forts, Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip

Fort St. Philip is a historic masonry fort located on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, about upriver from its mouth in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, just opposite Fort Jackson on the other side of the river. It formerly served a ...

, along with numerous small auxiliary fortifications. The two forts were of masonry and brick construction, armed with heavy rifled guns as well as smoothbore

A smoothbore weapon is one that has a barrel without rifling. Smoothbores range from handheld firearms to powerful tank guns and large artillery mortars.

History

Early firearms had smoothly bored barrels that fired projectiles without signi ...

s and located on either river bank to command long stretches of the river and the surrounding flats. In addition, the Confederates had some improvised ironclads

An ironclad is a steam-propelled warship protected by iron or steel armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. Th ...

and gunboats, large and small, but these were outnumbered and outgunned by the Union Navy

), (official)

, colors = Blue and gold

, colors_label = Colors

, march =

, mascot =

, equipment =

, equipment_label ...

fleet.

On April 16, after elaborate reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmisher ...

, the Union's fleet

Fleet may refer to:

Vehicles

*Fishing fleet

*Naval fleet

*Fleet vehicles, a pool of motor vehicles

*Fleet Aircraft, the aircraft manufacturing company

Places

Canada

* Fleet, Alberta, Canada, a hamlet

England

* The Fleet Lagoon, at Chesil Beach ...

steamed into position below the forts and prepared for the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip

The Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip (April 18–28, 1862) was the decisive battle for possession of New Orleans in the American Civil War. The two Confederate forts on the Mississippi River south of the city were attacked by a Union Nav ...

. On April 18, the mortar boats opened fire. Their shells fell with great accuracy, and although one of the boats was sunk by counter-fire and two more were disabled, Fort Jackson was seriously damaged. However, the defenses were by no means crippled, even after a second bombardment on April 19. A formidable obstacle to the advance of the Union main fleet was a boom

Boom may refer to:

Objects

* Boom (containment), a temporary floating barrier used to contain an oil spill

* Boom (navigational barrier), an obstacle used to control or block marine navigation

* Boom (sailing), a sailboat part

* Boom (windsurfi ...

between the forts, designed to detain vessels under close fire if they attempted to run past. Gunboats were repeatedly sent at night to endeavor to destroy the barrier, but they had little success. US Navy bombardment of the forts continued, disabling only a few Confederate guns. The gunners of Fort Jackson were under cover and limited in their ability to respond.

At last, on the night of April 23, the gunboats ''Pinola'' and ''Itasca'' ran in and opened a gap in the boom. At 2:00 a.m. on April 24, the fleet weighed anchor, Farragut in the corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

''Hartford'' leading. After a severe conflict at close quarters with the forts and ironclads and fire rafts of the defense, almost all the Union fleet (except the mortar boats) forced its way past. The ships soon steamed upriver past the Chalmette

Chalmette ( ) is a census-designated place (CDP) in, and the parish seat of, St. Bernard Parish in southeastern Louisiana, United States. The 2010 census reported that Chalmette had 16,751 people; 2011 population was listed as 17,119; however, th ...

batteries, the final significant Confederate defensive works protecting New Orleans from a sea-based attack.

At noon on April 25, Farragut anchored in front of the prized city. Forts Jackson and St. Philip, isolated and continuously bombarded by the mortar boats, surrendered on April 28. Soon afterwards, the infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

portion of the combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme vio ...

expedition marched into New Orleans and occupied the city without further resistance, resulting in the capture of New Orleans

The capture of New Orleans (April 25 – May 1, 1862) during the American Civil War was a turning point in the war, which precipitated the capture of the Mississippi River. Having fought past Forts Jackson and St. Philip, the Union was u ...

.

New Orleans had been captured without a battle in the city itself and so it was spared the destruction suffered by many other cities of the American South. It retains a historical flavor, with a wealth of 19th-century structures far beyond the early colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

city boundaries of the French Quarter

The French Quarter, also known as the , is the oldest neighborhood in the city of New Orleans. After New Orleans (french: La Nouvelle-Orléans) was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the city developed around the ("Old Squ ...

.

The city was in Confederate hands for 455 days.

New Orleans under Union Army

The Federal commander,Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler is best ...

, soon subjected New Orleans to a rigorous martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

so tactlessly administered as greatly to intensify the hostility of South and North. Many of his acts gave great offense, such as the seizure of $800,000 that had been deposited in the office of the Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

. Butler was nickname

A nickname is a substitute for the proper name of a familiar person, place or thing. Commonly used to express affection, a form of endearment, and sometimes amusement, it can also be used to express defamation of character. As a concept, it is ...

d "The Beast," or "Spoons Butler" (the latter arising from silverware looted from local homes by some Union troops, though there was no evidence that Butler himself was personally involved in such thievery). Butler ordered the inscription "The Union Must and Shall Be Preserved" to be carved into the base of the celebrated equestrian statue of General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

, the hero of the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the French ...

, in Jackson Square.

Most notorious to city residents was Butler's General Order No. 28 of May 15, issued after some provocation: if any woman should insult or show contempt for any Federal officer or soldier, she shall be regarded and shall be held liable to be treated as a "woman of the town plying her avocation," a common prostitute

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-penet ...

. That order provoked storms of protests both in the North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

as well as abroad, particularly in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

.

Among Butler's other controversial acts was the June hanging of William Mumford, a pro-Confederacy man who had torn down the US flag over the New Orleans Mint

The New Orleans Mint (french: Monnaie de La Nouvelle-Orléans) operated in New Orleans, Louisiana, as a branch mint of the United States Mint from 1838 to 1861 and from 1879 to 1909. During its years of operation, it produced over 427 million ...

, against Union orders. He also imprisoned a large number of uncooperative citizens. However, Butler's administration had benefits to the city, which was kept both orderly and his massive cleanup efforts made it unusually healthy by 19th century standards. However, the international furor over Butler's acts helped fuel his removal from command of the Department of the Gulf

The Department of the Gulf was a command of the United States Army in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and of the Confederate States Army during the Civil War.

History United States Army (Civil War)

Creation

The department was co ...

on December 17, 1862.

Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union general during the Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, ...

later assumed command at New Orleans. Under Banks, relationships between the troops and citizens improved, but the scars left by Butler's regime lingered for decades. Federal troops continued to occupy the city well after the war through the early part of Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

.

Civil War heritage

A number of significant structures and buildings associated with the Civil War still stand in New Orleans, and vestiges of the city's defenses are evident downriver, as well as upriver atCamp Parapet

Camp Parapet was a Civil War fortification at Shrewsbury, Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, a bit more than a mile upriver from the current city limits of New Orleans.

History

The fortification consisted of a Confederate defensive line about a mile ...

.

On Camp Street, Louisiana's Civil War Museum at Confederate Memorial Hall Museum

Confederate Memorial Hall Museum is a museum located in New Orleans which contains historical artifacts related to the Confederate States of America (C.S.A.) and the American Civil War. It is historically also known as "Memorial Hall". It houses ...

, founded in 1891 by war veterans, boasts the second-largest collection of Confederate military artifacts in the country, after Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

's Museum of the Confederacy

The American Civil War Museum is a multi-site museum in the Greater Richmond Region of central Virginia, dedicated to the history of the American Civil War. The museum operates three sites: The White House of the Confederacy, American Civil War M ...

.

Notable New Orleans people of the Confederate military

*P.G.T. Beauregard

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard (May 28, 1818 - February 20, 1893) was a Confederate general officer of Louisiana Creole descent who started the American Civil War by leading the attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Today, he is commonly ...

, Confederate general and inventor

*Judah P. Benjamin

Judah Philip Benjamin, QC (August 6, 1811 – May 6, 1884) was a United States senator from Louisiana, a Cabinet officer of the Confederate States and, after his escape to the United Kingdom at the end of the American Civil War, an English ba ...

, United States Senator, Confederate Attorney General, Secretary of War and Secretary of State

*Albert G. Blanchard

Albert Gallatin Blanchard (September 6, 1810 – June 21, 1891) was a general in the Confederate army during the American Civil War. He was among the small number of high-ranking Confederates to have been born in the North. He served on the ...

, Confederate general

*Harry T. Hays

Harry Thompson Hays (April 14, 1820 – August 21, 1876) was an American Army officer serving in the Mexican–American War and a general who served in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War.

Known as the "Louisiana Tigers," his brigad ...

, Confederate general

Notes

;Abbreviations used in these notes: :Official atlas: ''Atlas to accompany the official records of the Union and Confederate armies.'' :ORA (Official records, armies): ''War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies.'' :ORN (Official records, navies): ''Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion.''References

External links

New Orleans Civil War photo album

€”Article by Civil War historian/author Bryan S. Bush

Online exhibit about the Civil War

at

Louisiana State Museum

The Louisiana State Museum (LSM), founded in New Orleans in 1906, is a statewide system of National Historic Landmarks and modern structures across Louisiana, housing thousands of artifacts and works of art reflecting Louisiana's legacy of historic ...

Further reading

*Grace King

Grace Elizabeth King (November 29, 1852 – January 14, 1932) was an American author of Louisiana stories, history, and biography, and a leader in historical and literary activities.

King began her literary career as a response to George Washin ...

''New Orleans, the Place and the People''

(1895) *Henry Rightor

(1900) *John Smith Kendall

(1922) * Clara Solomon and Elliott Ashkenazi (ed.), ''The Civil War diary of Clara Solomon : Growing up in New Orleans, 1861-1862.'' Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press (1995) . *

Jean-Charles Houzeau

Jean-Charles Houzeau de Lehaie (October 7, 1820 – July 12, 1888) was a Belgian astronomer and journalist. A French speaker, he moved to New Orleans after getting in trouble for his politics in Belgium.

In the U.S. he continued his journalistic ...

, ''My Passage at the New Orleans Tribune: A Memoir of the Civil War Era''. Louisiana State University Press (2001) .

* Albert Gaius Hills and Gary L. Dyson (ed.), "A Civil War Correspondent in New Orleans, the Journals and Reports of Albert Gaius Hills of the Boston Journal." McFarland and Company, Inc.(2013) .

{{Authority control

Louisiana in the American Civil War

New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

19th century in New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...